LONGHOUSES

THE IROQUOIAN TRIBES The University of the State of New York — State Museum and Science Service — Albany

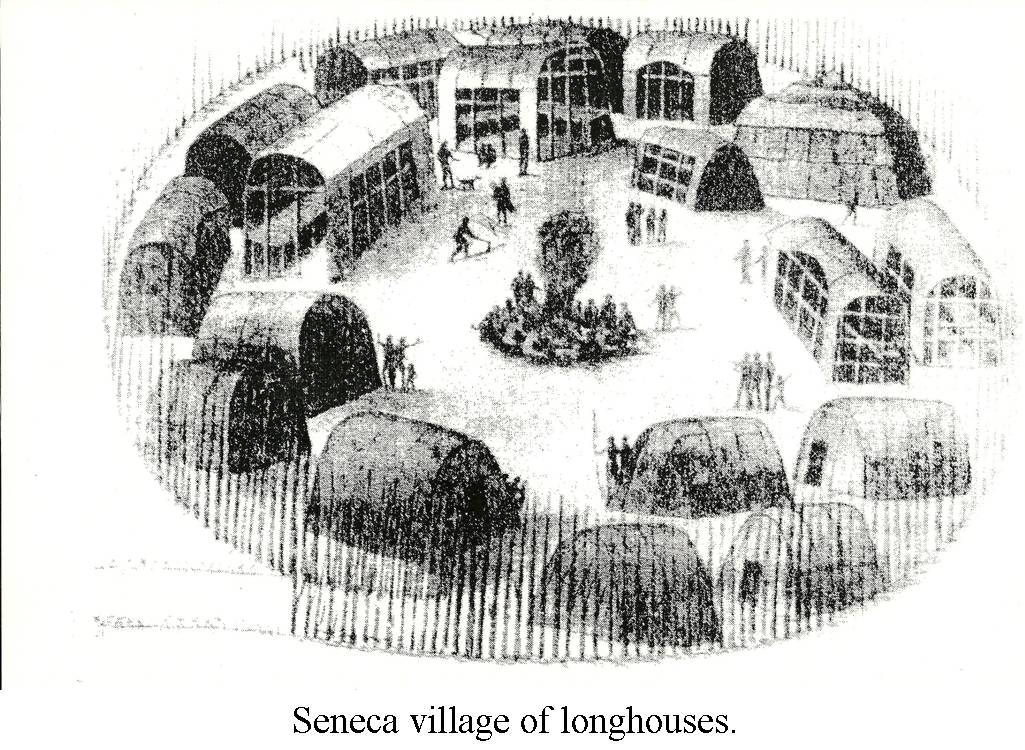

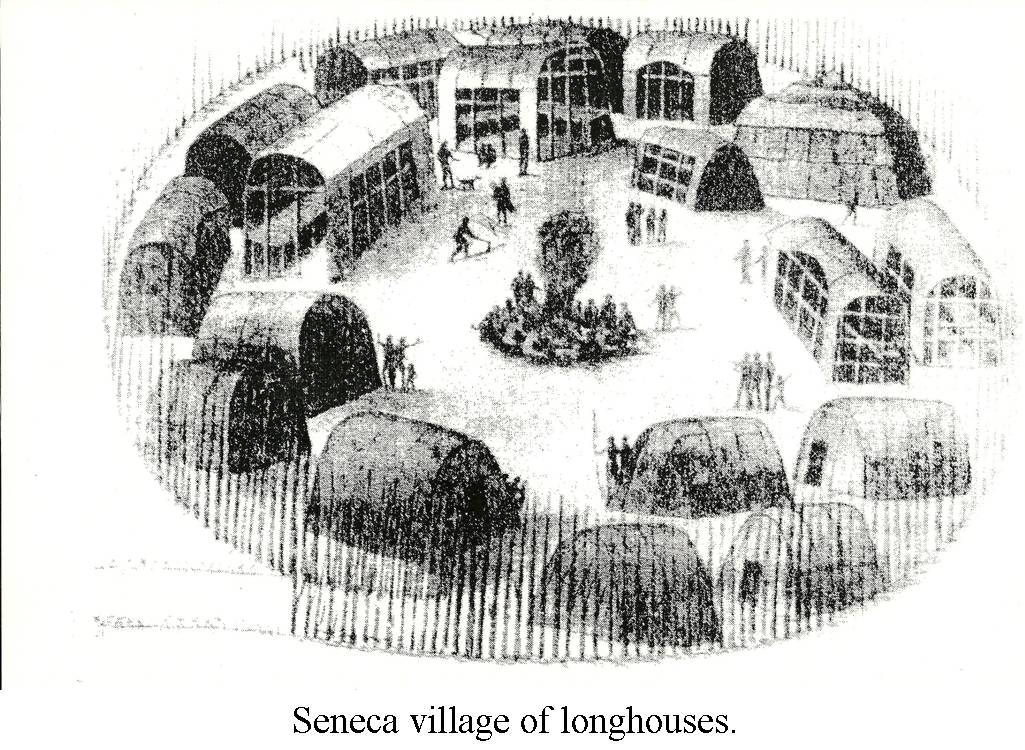

Iroquois houses, both single and communal dwellings, follow a basic longhouse plan. This form endured until about the end of the eighteenth century, when one-family, squared log cabins were used. Such homes are occasionally seen on present reservations, although they have largely been replaced by frame houses.

Iroquois houses, both single and communal dwellings, follow a basic longhouse plan. This form endured until about the end of the eighteenth century, when one-family, squared log cabins were used. Such homes are occasionally seen on present reservations, although they have largely been replaced by frame houses.

House building was a cooperative effort utilizing the organized labor of a work party of friends or relatives who could expect reciprocal aid in turn. Both men and women worked together, men on the heavier tasks, women in bark binding.

Construction began by setting upright in the ground, some four or five feet apart, small forked-top logs five to eight inches in diameter and some ten feet in height to form the outline of the dwelling. These were then bound together with cross poles by means of bark strips. Roofs, made without ridgepoles, were composed of a series of saplings bent into an arbor shape. In earlier times, they were almost flat, and the people, especially the children, congregated on them to watch village events. Small poles were tied lengthwise across the roof supports, and the house frame was ready for its bark cover. Overlapping roof slabs of bark were vertically placed, the remainder of the house being “shingled” horizontally. These sheets of bark were held securely between the inner poles of the house frame and an outer set of smaller poles placed lengthwise on the roof and upright along the walls.

Smoke holes, left at intervals of some twenty feet, were provided with bark covers, which could be manipulated from within by a long pole. A bark door, suspended from the top like the porthole covers on a ship, occurred at either end. Carved figures and paintings in black and red of animals representing the clans adorned the gable ends of the cabin fronts.

At either end of the house was a shed-like vestibule used for the storage of firewood and food in bark barrels and other containers and, through the removal of the bark side, for summer sleeping porches for the children. Entering the house through the vestibule, one came into a long corridor spotted at intervals with fires burning in shallow bowl-shaped hearths, one to each two families sharing opposite living compartments. Each compartment, about thirteen feet in length and six or so feet in width, was separated from the next in line by a bark walled storage closet for personal articles, cooking utensils, hunting gear, etc. Bunks for smaller children sometimes lined the closet walls.

The compartments of “rooms” open on the side toward the fire were furnished with a pole-and-bark-covered platform raised a foot or two above the floor. They were made comfortable for lounging and sleeping by an assortment of mats and furs, as well as deer and bear skins from which the hair had not been removed. A shelf overhead accommodated various goods, while from the rafters hung bunches of corn, braided together by the husks, and other dried foods.

The compartments of “rooms” open on the side toward the fire were furnished with a pole-and-bark-covered platform raised a foot or two above the floor. They were made comfortable for lounging and sleeping by an assortment of mats and furs, as well as deer and bear skins from which the hair had not been removed. A shelf overhead accommodated various goods, while from the rafters hung bunches of corn, braided together by the husks, and other dried foods.

SUGGESTED ACTIVITIES

*Use the drawing of the longhouse (shown above) as a coloring picture.

*Using the description of the interior of the longhouse found above, make a drawing of what is described.

*Make a model of a long house exterior and/or interior using craft sticks or twigs. Bark covering might be actual bark or brown felt.

Courtesy of the Warren County Historical Society

Iroquois houses, both single and communal dwellings, follow a basic longhouse plan. This form endured until about the end of the eighteenth century, when one-family, squared log cabins were used. Such homes are occasionally seen on present reservations, although they have largely been replaced by frame houses.

Iroquois houses, both single and communal dwellings, follow a basic longhouse plan. This form endured until about the end of the eighteenth century, when one-family, squared log cabins were used. Such homes are occasionally seen on present reservations, although they have largely been replaced by frame houses.  The compartments of “rooms” open on the side toward the fire were furnished with a pole-and-bark-covered platform raised a foot or two above the floor. They were made comfortable for lounging and sleeping by an assortment of mats and furs, as well as deer and bear skins from which the hair had not been removed. A shelf overhead accommodated various goods, while from the rafters hung bunches of corn, braided together by the husks, and other dried foods.

The compartments of “rooms” open on the side toward the fire were furnished with a pole-and-bark-covered platform raised a foot or two above the floor. They were made comfortable for lounging and sleeping by an assortment of mats and furs, as well as deer and bear skins from which the hair had not been removed. A shelf overhead accommodated various goods, while from the rafters hung bunches of corn, braided together by the husks, and other dried foods.